Hello and welcome to wild:health - or possibly wild:philosophy. I'm considering a name change (again) and would love to hear your thoughts on it. I think many of you reading this probably understand the challenge of accurately describing what we do in a way that maintains its nuance while at the same time doesn’t become alienating. The hell 👺 and beauty 💄 of online writing…

🎥 On a further note: Recently, I had the chance to talk to the fantastic and Jon Rhodes about the role of moral imagination in the metacrisis at RSA Oceania.

Today’s essay is my attempt to untangle why the cult of radical individualism leaves us feeling like failures, why “you-do-you” philosophy can’t fix a broken world, and how we might reclaim agency without buying into the myth that we’re solo acts in this mess.

We are raised in a culture of radical individualism and you-do-you self-fulfillment. We are told we can do anything, become anyone. The same applies to our philosophies: if we dig deep enough- questioning our ethico-onto-epistemological assumptions - we can supposedly create our own. There is even a book on creating your own religion.

This mindset is deeply rooted in mechanistic thinking that reduces the world - and ourselves - to projects to be engineered. Tara Isabella Burton, in her book Self-Made, argues that our belief in self-making stems from a “radical, modern reimagining of the nature of reality” - one that replaces a God-ordered universe, where roles were fixed by birth, with a worldview where the self is both creator and creation.

“The idea that we are self-makers is encoded into almost every aspect of Western contemporary life,”

Burton writes.

“We not only can but should customize and curate every facet of our lives to reflect our inner truth… We are all in thrall to the seductive myth that we are supposed to become our best selves.”

Yet when we try to find a philosophy - at least in the way I talk about it -we aren’t just attempting to create our best self. We’re also attempting to create - and enact - a better world.

Self-made is failing us

We have tested this self-made approach for long enough to realize that either the assumptions of self-making are wrong, or most of us are incapable and inherently flawed human beings. This is because, for many people, it feels like we don’t have full control over who we are becoming, despite all the possibilities available to us.

Self-help literature thrives on the assumption that we can do everything ourselves, yet we never seem to be quite able to achieve that.

The result is often self-blame, shame, and, in severe cases, hopelessness and depression.

As I recently shared, the approach of trying to use the tools that worked for others (e.g., the authors of self-help books) is deeply flawed. While we can learn from these books, the tools need to become part of us. We must immerse ourselves in them, like a veggie-chicken being buttered, adapt them to our context, make them our own, and align them with our ways of knowing, being, and acting in the world. Only then can they shape who we are and have a meaningful impact on us.

Returning to the increasingly widespread realization that there might be something wrong with the "you-do-you-and-you-can-become-anyone" approach, we can observe a few different reactions:

Some double down on the belief in solitary mastery over one’s destiny, insisting that any inability to transform lies solely in our own shortcomings.

Others swing to the opposite extreme, arguing that our environment - laden with oppressive systems and structural inequities - is the dominant force affecting our flourishing.

Still others focus on a therapeutic narrative: the idea that if only we could repair the damaged parts of ourselves (whether from trauma, developmental imbalances, or other deficiencies), personal growth would finally be possible.

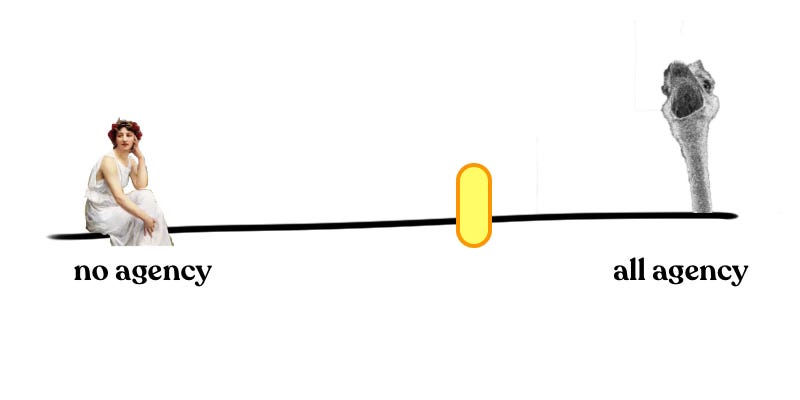

At its core, the different approaches circle around agency: Is it something that resides entirely within us, something that emanates only from outside, or something that exists in the relation between the two? Do we have no agency, complete agency or everything in between?

A matter of agency

Agency is our ability to (a) make choices and (b) to act on them. One of the core challenges of our time is that even if we do make choices, such as wanting to live a regenerative lifestyle, we are often unable to act upon that choice. The b in agency has thus become difficult. But that’s another story and today, let’s focus on (a): the choice.

A relational approach to agency tries to reconcile the differences by refusing the binary of “self vs. system” altogether. Through a relational lens, the self is neither sovereign nor passive, but a relational process - a dynamic entanglement of biology, culture, ancestors, ecosystems, and choices. We are not self-made, but world-made. Our becoming is co-authored by the air we breathe, the stories we inherit, the microbes in our gut, and the economic systems that shape our opportunities. To “become anyone” is not an act of willpower, but an act of intra-acting reciprocity. For example, a seed holds potential, but its growth depends on soil, rain, and sunlight - all of these are beyond its control. Similarly, our agency flourishes only when nested within relationships of care: to land, community, and the more-than-human world.

From a relational perspective then, our task is not to fix ourselves in isolation, to let go of the you-do-you-and-you-can-become-anyone-approach, and to tend the conditions that allow life - our own and others’ - to thrive, listening for the ways our self-making is always a collaboration.

Agency in our philosophies

If our “self-making” is always a collaboration, then crafting a personal philosophy cannot be a solitary act of willpower.

As I have recently written:

Philosophies are actual occasions - with their own agency. Your philosophy isn’t a puppet you control, it’s a presence you collaborate with. It evolves as you meet new people, read new books, or walk through a forest and feel your separateness dissolve…..

A living philosophy isn’t a monologue - it’s a polyphonic conversation. It listens as much as it speaks. It’s accountable to the communities (human and otherwise) it impacts.

To have a philosophy, then, is to host a lichen: part you, part other, wholly intra-dependent.

This shifts philosophy from a noun to a gerund: not truth but truthing, not being but becoming.

This doesn’t mean surrendering agency. It means recognizing that agency is always shared. Just as a gardener collaborates with sunlight, soil, and seasons, we collaborate with the philosophies that root us. Sometimes they surprise us. Sometimes they wound us. Sometimes they compost into something new. But they are never passive.

(No)/all agency

I love thinking through a relational lens, but as someone who grew up deeply embedded in the WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) world’s thinking, being, and acting, I often find it challenging to translate this into everyday life.

As a "fun" side story: while my Ph.D. focused on a relational approach, it was only after publishing several papers and nearing the end of my writing that I realized I had written about relational approaches without grounding myself and my research approach in a relational way.

To my understanding, this is exactly what Burton means when she talks about modern self-making: we give the impression of being something without actually embodying that change. We talk about something - which is easy - and forget to be that something.

And I understand why; it's messy and requires time and effort.

So, how can we embody the space between having no agency and full agency?

Holding our agency lightly: Without concrete data to support this, my observation is that people who act as if they have significant agency tend to be not only more "successful" in their endeavors but also more satisfied with life. Research also shows that agency is positively correlated with well-being. So, while we acknowledge that we don’t have the agency to choose our philosophy, we can act as if we do and remain open to change.

Making use of the agency we do have: While our agency is never fully ours, we can't deny that we do possess some degree of it. Becoming aware of this is part of life becoming aware of itself- as an agent (I highly recommend checking out

’s Microphilosopher to make use of that agency).In practice, this means developing a philosophy with the humility to treat it as an ongoing experiment: Rather than viewing our beliefs as unchangeable edicts, we learn to see them as provisional experiments. We test them in the messy realm of everyday life, learn from both immediate consequences and unforeseen global impacts, and refine them through honest, vulnerable reflection. This practice not only makes room for organic growth but also recognizes that our personal evolution is inextricably linked to the evolution of our social and environmental contexts.

We must become hyper-attuned to the feedback we receive: This includes not only the insights from our local communities but also those from the far reaches of our entangled world. This feedback allows our philosophy to remain dynamic, ensuring that our aspirations are continuously recalibrated in light of new insights, challenges, or opportunities.

We need mentors and communities that help us critically assess the values we hold and the narratives that have shaped us: Through others, we can discern which aspirations are genuinely ours and which are cultural impositions, ultimately learning to strive for authenticity that is life-affirming rather than a performance crafted for approval.

This is what makes us human: The process of "finding a philosophy" is actually a process of living philosophically, where the search itself is the discovery. If our self is continuously in conversation with others - be they fellow humans or more-than-human beings, stories, and cultures - such a perspective draws us away from the exhausting mandate to constantly reinvent ourselves. Instead, we move toward understanding personal evolution as a slow, patient, and deeply humane process. I believe this is what makes us human (and distinguishes us from AI). This requires that we…

Slow down: Returning to the messiness, time, and effort involved. As this is what makes us human, it’s also a lifelong process - navigating who we are and who we are becoming (or becoming-with). We can’t do this between dinner and dessert. In my experience, it takes time, commitment, and effort. I am well aware of how unappealing this might seem to most people. We are so conditioned to seek comfort and quick fixes that anything requiring effort feels draining. However, research indicates that it’s through effort that things become meaningful.

As Michael Easter says in his book The Comfort Crisis: Embrace Discomfort To Reclaim Your Wild, Happy, Healthy Self:

“Comforts and conveniences are great. But they haven’t always moved the ball downfield in our most important metric: happy, healthful years. Perhaps existing only in our increasingly overly comfortable, overbuilt environment and always obeying our comfort drives has had unintended consequences and caused us to miss profound human experiences.”

The myth of radical individualism promised mastery but delivered fragility.

To forge philosophies that regenerate us, may we abandon the fiction of the self-made self.

Agency is a matter of integrating diversity: human and nonhuman, past and present.

This doesn’t mean surrendering to fate.

May we tend to the relationships, ideas, and ecosystems that let our agency rot, root and bloom. It’s messy. Slow. But it’s the effort itself that seeds meaning.

Philosophy isn’t just a manifesto we write - it’s a life we live, one imperfect, entangled choice at a time.

If you think that a friend or someone you know would benefit from reading this, please share.🌱🌻

Narcissus is a traditional image/metaphor of the separate individual. Narcissus at the pond is not only a metaphor for the separative ego itself , but it is also a specific metaphorical reference to the characteristic human preoccupation of staring at the mind. The image in the pond is the mind, and the solitary or separative activity of avoiding relationship, which is the seed-activity that leads to the breakdown of the whole or the totality, including the human collective.

As a result the world becomes a mad gathering of egos, preoccupied with separateness, with self-concern, with separative impulses, desires, and intentions (many of which are self-destructive) and with every kind of search for both self-fulfillment and release. The ego-principle of universalized separateness and separativeness, is, to the social domain of humankind what cancer is to the individual body. Uncontrolled division is the destructive opposite of wholeness or indivisibility, whether of the individual or of the collective

I'd like to thank and congratulate you. Personally these recent pieces are very pertinent and useful for thinking about major life problems with implications also for my views about social and political issues.

Maybe a crisis of agency, for some approaching or reaching a collapse of agency, is far more common than most of us are aware, as the webs which held together and sustained collective and thus individual lives of meaning have reached such a point of disintegration that we struggle with the how and the why.