Hello and welcome to rewilding philosophy. Your letters for ekophilosophical health in the Anthropocene.

Life is about the choices you make. So they say.

Have you ever had to make a difficult choice in your life?

Of course, you have.

You might have noticed that some choices come easily, while others are much more challenging. The tougher ones defy simple calculations or a quick pro and con list.

In Wild Problems: A Guide to the Decisions That Define Us Russell Roberts defines these sort of choices as “wild problems”.

He writes that while tame problems are clear and objectively assessed, like how to get to Chicago from New York, wild problems are subjective and hard to measure, like wether to go to Chicago in the first place. Tame problems can be verified; results can be replicated. For wild problems, there is no manual, road map, recipe, or algorithm for success.

“Wild problems resist measurement. What works for you might not work for me, and what worked for me yesterday might not work for me tomorrow. Wild problems are untamed, undomesticated, spontaneous, organic, complex.” Russell Roberts

Wild problems are usually the ones that determine who we are. While not all of them have to be hugely important - like wether to visit a friend in Chicago - they nonetheless define what sort of person we are at our core. They reveal what we care about, what we prioritise and what sort of person we want to become.

“The choices we make in the face of wild problems produce more than just a stream of costs and benefits going forward. Those choices define who we are and give our lives meaning when they work out well. Even the challenge of facing them when they don’t work out well is part of living as a human being.” Russell Roberts

The Anthropocene is characterised by wild problems in which choices are not only about our personal preferences, but a whole range of intra-acting other beings that have agency and inevitably penetrate our choices and decision making — whether hyperobjects like global warming and species extinction or the microbes lining our guts.

We have no simple solutions for many decisions within the Anthropocene. Simple calculations fall short as entanglements can create cascading effects on other parts of the system that we were blind to take into account. We fail to realize where to even begin.

Nora Bateson says that a

“Combining in new ways across and among contexts is required in these runaway circumstances—not static, calculated, predetermined solutions.“

But I am getting ahead of myself.

Understanding the Nature of Wild Problems

The way wild problems play out in my own life is in those seemingly minor efforts toward a sustainable lifestyle, like deciding whether to fly, taking my own cup everywhere, or buying only local and vegan food. You get the picture.

These choices seem not worth the effort if I reduce them to a calculation of my carbon footprint and compare that to the overall impact on the planet.

Yet, when I take into account their wildness, I recognise how each choice is entangled in a web of relationships. A seemingly trivial choice such as choosing to bring my own cup is charged with implications about waste production and the health of our oceans. The convenience of single-use plastics comes at the cost of long-term ecological harm, impacting marine life and ecosystems far beyond my immediate surroundings.

On one side of the scale, I can triviliaze simple, everyday choices and reduce them to a mere number. On the other side of the scale, the choice becomes wilder than my wildest dreams allow me to think. The decision to drink a cup of coffee suddenly implicates global warming, species extinction, inequality and the use of pesticides.

Who on earth is supposed to turn every minor decision into a full-on major life choice that we typically associated with major, infrequent life decisions such as which job to take, where to move, or whom to have family with (if any)?

No wonder we are overwhelmed and feel incapable of doing anything.

Navigating Wild Problems

There is no simple answer to the above challenge. If there were, we’d have the whole thing of the Anthropocene solved already.

In fact, the whole problem might lie in trying to find a “solution” in the first place, a solution being a way out of the situation we are in. The urge that many of us experience to find a solution shows our inability to just be with uncertainties. Though the word "solution" comes from the Latin word "solutio," which means "a loosening" or "untying." Maybe it’s more about a loosening or letting go of a problem instead of a jumping to conclusions. It’s exactly through leaning into those uncertainties - without leaping to solutions - that real change emerges (something we practice in the PhilosophyGyms, by the way - if you are interested to join, let me know, there will soon be a second cohort).

Despite this disclaimer, there are some concepts and ideas we can use to make this easier. These concepts are specifically about how to perceive of wild problems in order to make sense of them.

If theory isn’t your thing, skip the next two short sections and jump ahead to “The Five Dimensions of Being.”

Four Ways of Knowing

The first helpful model comes from cognitive scientist and philosopher John Vervaeke, who identifies four ways of knowing: propositional, procedural, perspectival and participatory. If you haven’t heard of them yet, don’t worry, it’ll become clear in a minute.

To deal with wild problems, I can deviate from my default way of knowing - which for me is propositional knowing - and include other ways of knowing.

Propositional Knowing: involves understanding factual information about the environmental impact of choices. It helps me identify the tangible effects of actions like using single-use plastics, providing a rational basis for my sustainable decisions.

Procedural Knowing: focuses on developing practical skills and habits for sustainability, such as learning to consistently carry a reusable cup or source local food. Practicing these skills makes sustainable living more automatic and less burdensome.

Perspectival Knowing: Through perspectival knowing, I can appreciate the broader context and interconnectedness of my choices. It enhances empathy towards affected ecosystems and future generations and encourages my decisions that align with a deeper understanding of my place in a complex world.

Participatory Knowing: involves being actively engaged in a community and the more-than-human world to foster a sense of belonging and accountability. Participatory knowing helps me feel part of a larger movement toward sustainability, making each small action feel more significant and connected to broader ecological and social systems.

4E cognition

Another helpful model to consider is 4E cognition, which stands for embodied, embedded, enacted, and extended cognition. 4E cognition challenges traditional cognitive science views that primarily focus on the brain as the locus of cognitive processes and includes other dimensions of cognition. We don’t just think with our brain. We don’t make decisions just with our brains.

Embodied Cognition: emphasizes the role of the body in shaping cognitive processes. Sustainability practices, such as carrying a reusable cup or choosing to walk instead of drive, engage the body directly, helping reinforce sustainable habits through sensory and physical experiences.

Embedded Cognition: focuses on the context in which cognition occurs. Recognizing that actions take place within specific environmental, social, and cultural contexts can clarify how our choices are influenced by and impact these systems.

Enacted Cognition: underscores the idea that cognition arises through active engagement with the world. By experimenting with and adapting sustainable practices in response to real-world feedback, we can more dynamically address the sustainability challenges we face.

Extended Cognition: suggests that cognitive processes can extend beyond the individual to include tools and technologies. Utilizing resources like carbon footprint calculators or community networks extends our cognitive capabilities, supporting more informed decisions.

Both of these models make it clear that merely taking into account calculations or the attempt to reduce our decision making to a numbers game is insufficient. Our knowing encompasses more.

To make it more practical, I want to introduce a third idea.

Five Dimensions of Being

Based on the models that we have just learned about, we can enrich our decision-making by engaging multiple dimensions of our being—not just cognitive reasoning. A multifaceted approach is to integrate our head, heart, hand, belly, and sex into this:

Head (Cognitive): The head represents the logical, analytical aspect of our decision-making, where we engage with facts, data, and information. It's about understanding the environmental impact of choices like flying or using plastic.

The questions to ask yourself here are: what are the facts? What does the data say?

While indispensable, relying solely on the head can reduce complex issues to numbers, missing - as most of us know - the richness of our lived experience.

Heart (Emotional): The heart brings empathy and emotional awareness into our decision-making. It allows us to connect with the consequences of our actions on other beings and future generations.

“Heart” refers to a deeper portal of profound interconnectedness and awareness that exists between humans and all living things. Centering oneself there results in humble, wise, connected ways of being and acting in the world. Indigenous peoples have cultivated access to this source as part of a deep experience and awareness of the profound interdependency between the natural and human worlds. To access it, you must drop out of the relentless thinking that typically occupies the Western mind.

When accessed, this portal provides the inner wisdom that keeps us in right relationship with all of life, thus ensuring our long-term survival and well-being, individually and collectively. Our fallible thought processes regularly deceive us. Yet, when guidance or information comes from the heart, it can be relied upon and has impeccable integrity. . . .” Ilarion Merculieff

The questions to ask yourself here are: how do my choices affect the well-being of other people and creatures? What emotions arise when I consider the impact of my decisions?

While the heart provides vital insight into the human aspect of sustainability, relying solely on emotions may lead to decisions driven by temporary feelings rather than enduring commitments.

“Anyone who wants to be all head is as much a monster as one who wants to be all heart.” Johann Gottfried Herder

Hand (Practical): The hand signifies our capability to implement and engage with the world practically. It's about knowing how to integrate sustainable practices into daily life, from riding a bike instead of driving to creating less waste. The hand reflects the skills we develop to act in alignment with our values, learned through embodied practice.

The questions to ask yourself here are: which practical capabilities and abilities do I have in this situation? What is it that I can actually do? Which practical skills might I need to develop?

While essential for enacting change, focusing solely on practicality can overlook the underlying beliefs and emotions that motivate our behavior.

Belly (Intuitive): The belly refers to our gut instincts and the deeper, often subconscious, relations we have with the world. Our belly taps into the intuition that comes from being attuned to our human and more-than-human community, as well as to spirit world. It speaks to the inherent sense of rightness or wrongness we feel in various situations, guiding us in complex decisions without explicit reasoning.

The questions to ask yourself here are: what does my intuition tell me about my choices? How can I cultivate a deeper connection with my instincts and the more-than-human world?

While intuition can offer fantastic guidance, relying purely on gut feelings may sometimes lead to decisions that lack a rational or practical grounding.

Sex (Creative): This dimension represents the creative and life-affirming energies that drive us. It embodies the desire for connection, creation, and continuity with the world around us. It’s the energy that Zak Stein and others base their theory of Cosmo-Erotic-Humanism on. It’s also what Andreas Weber refers to as our Eros - our drive to relate to the world.

“Eros is wholeness and interconnectivity. It is the essential nature of a cosmos whose core truth might well be: reality is relationship.” Marc Gafni

The questions to ask yourself here are: what is it your deeper values long for? What’s the driving force in your life? What truly excites you?

When we tap into wild problems, it’s wise to try to listen all five dimensions of our being and see what they have to say about the challenge.

When you do that, it’s likely that each of them says something different. For example, while your belly might tell you to put your savings into a conventional bank because it likes feeling safe and secure, your heart might tell you that you should invest in a project on renewable energies, which is risky, but really aligns with your drive to contribute to the greater good.

One example from my own life is around air travel. I frequently face the decision about whether to significantly reduce my carbon footprint by minimizing my air travel. My head then weighs the environmental data and clearly points towards reducing flights as the logical choice (if I just focus on my individual impact). My heart feels called to travel often - and far - especially to the US where I lived for some time and where a lot of the people I love deeply live. My hand though can focus on practical alternatives, like choosing local destinations accessible by train, while my belly feels a deep sense of guilt whenever I consider boarding a plane. The eros dimension inspires me to expand and also to consider the planetary health of all beings, urging me to find joy and adventure in discovering the local.

What’s the decision then? Do I fly or not.

Well, we can easily jump to the conclusion that it’s best when all five dimensions are aligned - that only then can we make a good decision. The American psychologist Carl Rogers would certainly agree to that. He suggested that it is "congruence" - which refers to the harmony between a person's identity, experiences, and actions - which makes us feel psychologically well. If these elements are misaligned, it can cause psychological distress. While his elements are not the same as the dimensions I introduce above, the assumption of alignment is nonetheless prevalent.

I think there are other ways forward.

Just like resilient ecosystems or good democracies rely on diversity, so too do the different dimensions within us. The different dimensions within us are meant to be contradictory to find a comprehensive next step.

Experiencing tensions among the head, heart, hand, belly, and sex is beneficial because these tensions foster deeper introspection and creativity in our decision-making processes.

The inner diversity mirrors the complexity of our outer world, such as within ecological and social systems.

When faced with conflicting inputs from these dimensions, we can perceive that as encouragement to consider and integrate multiple perspectives rather than defaulting to a simplistic or one-dimensional solution.

I haven't flown in the past five years. However, it's quite likely that I will travel to the US within the next year. Each situation requires weighing the different dimensions of my being differently, and it's not necessary for all of them to agree on this decision.

So there you have it. A way to approach wild problems. Not a way to solve them, but a way to live with them.

Very unsatisfying. I know.

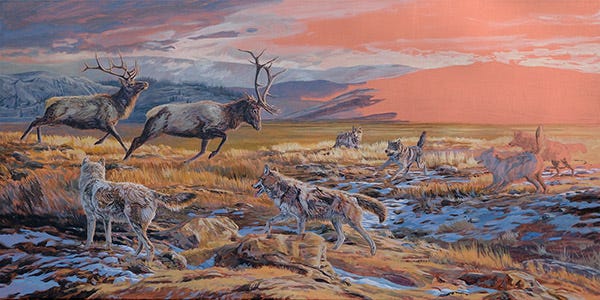

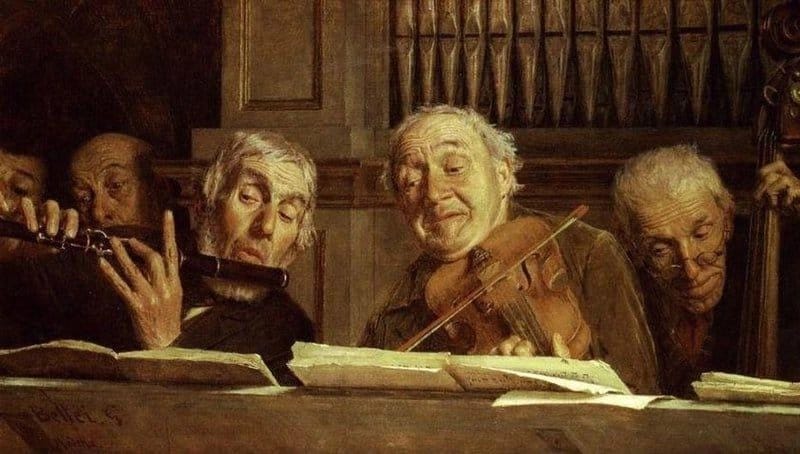

While the following analogy has almost become a cliché, I use it nonetheless, because it’s so fitting: navigating wild problems is less like an orchestra and more like a Jazz concert in which every instrument has its own tempo and tune, and somehow, you're supposed to make music out of it. Instead of striving for a flawless symphony, it’s full of unexpected twists and improvisations. A cacophony of beautiful madness. Because at the end of the day, maybe it's not about solving wild problems at all, but about diving into the wildness itself, to - as Daniel Wahl says - “live the question”.

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.” Rainer Maria Rilke

If you are enjoying this newsletter, maybe there is a friend you would like to forward this to.

I love that here is a beautiful exposition of the different aspects of being and knowing that I can relate to; that resonates with me — that I can take in with my heart as well as head. Ending without resolution feels … well … realistic. I recognise and deeply value the striving towards accepting uncertainty, and towards the positive experience of tension between these various modes of being, and also I have qualifications, that follow below.

“The urge that many of us experience to find a solution shows our inability to just be with uncertainties.” “Urge” and urgency invite me to consider time discounting. “Uncertainties” brings up statistical thinking. We all need to make decisions sometimes. Could it be comfort with a difficult choice that we are looking for, rather than the promise or guarantee that a choice will be the right one? And, for sure, making any choice (that isn't just a test for knowing “the right answer”) comes with uncertainty: will it work out for the best? So, how about a middle way between the two extremes (and yes, I'm exaggerating for effect here: you haven't put it like this at all) not needing a definitive solution, not just passively accepting being uncertain, but making choices based on time discounting and statistical reasoning? Maybe this speaks to the question of what middle ground there may be between tame and wild problems as you have described them. It's not only that I don't see a clear dividing line between tame and wild problems, but also that I find the region in between them of great interest. What you say around “loosening or letting go of a problem” makes sense — I feel I would see it as viewing a situation from different perspectives, and only in some of those perspectives does it look like a problem. In others, an opportunity … “There is no simple answer …” indeed.

Returning to the urge … if someone has an inner need to be correct all the time, that could also disable their ability to be with uncertainty about their own views. In this case, I wholeheartedly support the move towards accepting uncertainty, while noting that if this need is psychologically embedded, the journey may not be easy. Support is needed here.

And another case: the inability to just be with uncertainty may be to do with a more basic need. I don't want to be asking people to be comfortable with uncertainty about where their next meal is coming from, whether their house may be destroyed in a war tomorrow, etc. So, for me, the desirability depends on circumstances. Some physical security on the lower steps of Maslow's triangle are called for. These problems may be “wild” in the sense you adopt, but equally they cry out for solution. For sure, some people take religious faith to the point of total reliance on a higher power. For most, the received wisdom is more like https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trust_in_God_and_keep_your_powder_dry and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/God_helps_those_who_help_themselves

“Experiencing tensions among the head, heart, hand, belly, and sex is beneficial because these tensions foster deeper introspection and creativity in our decision-making processes.” Well, “it depends”, I'd say. “can potentially be beneficial”, I'd thoroughly agree, if you are blessed with the inner qualities and outer situation that allows that deeper introspection and creativity. But I can think of different situations where the outcome is not so beneficial.

Say you've been brought up with small-t trauma related to chaos in your family or community life. Probably you've developed some mental protections against inner chaos. Pushing people to recognise to see what looks like chaos inside themselves may, I'd guess, be rather hazardous. I can imagine it leading either to unbearable stress, or to submission to whatever force seems the strongest at any particular time.

I can imagine that someone who has difficult outward circumstances might be overwhelmed by those tensions, and crack. Not that we are determined by our outward circumstances. But in an increasingly complex world, where day-to-day living seems to get more and more demanding, the prospects may not be good.

Much has been written about the combination of challenge and support. What my points come down to is mainly, if people have enough support, they are much more likely to be able to live with uncertainty. (Though, uncertainty around the support itself? I'm not so sure.) I have a persistent sense that I am actually very lucky in being relatively materially comfortable and secure, and perhaps that contributes to my internal sense of security. How do we work towards a society where all good people have basic security, and sufficient support to take on the challenges? For me, that is to do with enabling sharing, living humbly, voluntary simplicity; and linked to that, to living with other people who have enough capacity to offer the necessary psychological, moral, maybe philosophical support. Then we can be more at ease with asking people to welcome the challenges of uncertainty and the tension. That, in turn, needs practice with the skills that are needed to live well with others. This is not a new theme for me — moving from focus on the individual to focus on the collective!

I also love the identification of Sex with the creative. As well as the instinctive sexual attraction, with the urge to procreate, for me this kind of attraction carries over to people I feel the potential to co-create with, other than biologically.

You follow on: “The questions to ask yourself here are: what is it your deeper values long for? What’s the driving force in your life? What truly excites you?” I long to be in co-creative relationship with people where our aims, our visions, relate well together, and are complementary and in synergy. Though I guess there will always be elements of fear remaining in me, and these do and will drive some of my reactions, I really want the driving force in my life to be love: love of others, love of humanity, love of truth, love of nature, love of beauty, love of the planet, love of life, love of the spirit of love. What truly excites me is when I hear and see actions or words (whether coming through me or someone else) that contribute to the love, the life, the learning, the growth and development, of other people; and when I feel in a collaborative creative flow — within the essential context of love, that also applies to sexuality.

You might be interested in the four-fold epistemology that lies at the heart of co-operative inquiry:

Experiential knowing brings attention to bear on the lifeworld of everyday lived experience. This is that aspect of knowing that arises through face-to-face encounter, perception, empathy, and resonance with a person, place, or thing. Experiential knowing is essentially tacit, often inaccessible to direct conscious awareness, almost impossible to put into words. Through experience we have direct access to the core of existence; it is the touchstone of the inquiry process and deepens through that process.

Presentational knowing can be seen as the first clothing or articulation of experiential knowing: we tell the story, make a sketch, gesture, sing or dance as an expression of our experience, often bringing it into consciousness for the first time to ourselves and to others as we do so. Such a spontaneous narrative can then be intentionally articulated and developed through creative writing and storytelling, drawing, sculpture, movement, dance, all drawing on aesthetic imagery.

Propositional knowing is knowing ‘about’ something in intellectual terms, in ideas and theories. It is expressed in propositions and statements which use language to assert facts about the world, laws that make generalisations about facts, and theories that organise the laws. This propositional form of knowing is the main kind of knowledge accepted in modern society.

Practical knowing is knowing ‘how to’, knowing-in-action. Practical knowing has a quality of its own, ‘useful to an actor at the moment of action rather than to a disembodied thinker at the moment of reflection’. At the heart of practical knowing is skilful doing, which may be beyond language and conceptual formulation. For a fuller description of the inquiry process go to https://www.peterreason.net/wp-content/uploads/Extending-co-operative-inquiry-beyond-the-human-ontopoetic-inquiry-with-rivers.pdf and Learning How Land Speaks peterreason.substack.com