Welcome to rewilding philosophy, your newsletter on ekophilosophical health for our times. One of the things I am very challenged about, which threatens my sense of ekophilosophical health, is my seemingly insatiable desire for more —whether it's things or experiences. While at the same time one of my core values is to reduce the harm I cause to the environment. The result is a mushy mess of conflicting values.

I see myself as a minimalist. Yet, I want everything. I can’t make a decision of what I want to do and who I want to be, because I want it all. I want to be a professor, and I want to be an artist. I also want to be a dancer. And a Mundharmonika player. And an entrepreneur. I want to found a university of applied philosophy. I want to travel the world and I want to settle down. I want a farm and I want to be free of any obligations. I want a dog and a cat.

“You see, I want a lot. Perhaps I want everything: the darkness that comes with every infinite fall. And the shivering blaze of every step up. So many live on and want nothing, and are raised to the rank of prince by the slippery ease of their light judgments. But what you love to see are faces That do work and feel thirst.” Rainer Maria Rilke

I know I am not alone with this.

And our culture is not making it easier. We are raised to belief that we can have it all and that we are entitled to it, too. I often wonder how different it might have been in times when people were born into predetermined professions and places, following that path for a lifetime (a reality still for many across the globe).

I came across four - very different - theories that might explain or at least help me understand my apparently insatiable desire for everything.

Mimetic Theory

“What Jesus invites us to imitate is his own desire, the spirit that directs him toward the goal on which his intention is fixed: to resemble god the father as much as possible” René Girard

René Girard, a French historian, literary critic, and philosopher, introduced Mimetic Theory. This concept challenges the notion that human desires spring spontaneously. Girard posited that desires are inherently imitative, shaped by others' influences rather than arising independently. According to him, culture primarily evolves through the replication of desires rather than the replication of material possessions. Desires, he argued, aren't discrete, static, and fixed but fluid, open - ended, dynamic, and volatile.

This imitation can lead to conflicts and rivalries, particularly when individuals desire the same object or goal. According to Girard, mimetic desire can escalate into violence and societal tension. However, he also noted its potential for positive outcomes. It can foster unity among people when directed towards a common good, creating a cycle rooted in abundance and reciprocal giving, thereby transforming societies.

In today's world, smartphones serve as potent dream machines, tapping into our neurological addictive tendencies. However, Girard would argue that the true peril lies in our addiction to the desires propagated through these devices. The constant exposure to others' desires through smartphones accumulates myriad desires within us, perhaps contributing to the feeling of wanting everything.

Maybe I can’t stop wanting everything, because everyone desires something. And because I have constant access to all those people desiring something, all these somethings accumulate in me into everything.

Dopamine

The three most common explanations - and for me the least interesting ones - for our drive for more are biochemical, evolutionary, and social factors.

One significant biochemical explanation involves the role of neurotransmitters such as dopamine. Dopamine is associated with the brain's reward system and plays a crucial role in motivation, pleasure, and reinforcement of certain behaviors. When we experience something rewarding or pleasurable, dopamine is released in our brains, reinforcing the behavior and encouraging us to seek more of that experience.

“When we experience pleasure, dopamine is released in our reward pathway and the balance tips to the side of pleasure. The more our balance tips , and the faster it tips , the more pleasure we feel.” Anne Lembke, Dopamine Nation

Moreover, our evolutionary history might also play a role. Throughout human evolution, the pursuit of resources like food, shelter, and mates was essential for survival and reproduction. This instinctual drive to secure resources for survival might manifest today as a drive for more wealth, possessions, or status.

Lastly, social and cultural influences are also said to contribute significantly to our drive for more. Societal norms, peer pressure, and cultural values often emphasize the pursuit of success, wealth, and material possessions. This societal conditioning can further fuel our desire for more, as we seek to meet perceived societal standards or expectations.

Perhaps I'm essentially a biochemical machine shaped by evolution, entrenched in a society wired for a singular pursuit: more. Not because there is any aesthetic aspect in wanting, but because it's simply a fundamental aspect of my (co-)constitution.

Eros

Eros, the Greek god of love, was considered a tragic figure in antiquity. He was not the god of pleasurable satisfaction, but of emotional intensity that burned just as hotly, if not more so, when unsatisfied.

Integral philosopher Mark Gafni suggests that Eros embodies aliveness, where everything becomes fascinating for those truly alive. It's not about the nature of the experience—be it piercing pain, fleeting pleasure, profound grief, or captivating beauty—rather, it's about living with an erotic intensity across all aspects of existence. Our drive for aliveness is our Eros that drives us towards experiencing more of the other.

Eco-philosopher Andreas Weber sees Eros in the natural unfolding of living systems, emphasizing the fundamental longing for connection evident in molecules, cells, bodies, and landscapes. In each of these, the drive, desire, and longing for attachment to the other is foundational. This drive to relate to others is what makes us feel truly alive.

“Biology is the erotic science par excellence, because a living being is an erotic process: It transforms itself through contact with others, imagining new relationships out of each existing one, desiring more life, unrelentingly seeking a connection to the whole of which it is both concentration and unrepeatable instantiation.” Andreas Weber, Matter and Desire

In these perspectives, the universe is a love story where our yearning for more emerges from our love, or Eros, for the entirety of existence. Reality, in its entirety, is allurement, and our impulse for "everything" represents the same erotic drive that moves all of existence.

Maybe desiring everything is innate, driving the world itself, rooted in a continuous aspiration to merge with the world driven by love. If this holds true, it suggests we've veered slightly off course, misdirecting our desires toward material possessions like SUVs and popcorn, overlooking the deeper connection with the world.

Analytic Idealism

“Mind and matter do not reside in the same level of explanatory abstraction. In fact, mind is the ground within which, and out of which, abstractions are made. Matter, in turn, is an abstraction of mind.” Bernardo Kastrup, The Idea of the World

I came across analytic idealism a few years ago through philosopher Bernardo Kastrup. At its core, Analytic Idealism challenges the assumption of materialism, which asserts that the physical world is primary and that consciousness somehow emerges from physical processes. Instead, Kastrup argues that consciousness is the foundation of reality. He posits that what we perceive as the external world is, in essence, a manifestation or expression of consciousness. The material world then is a construct within consciousness.

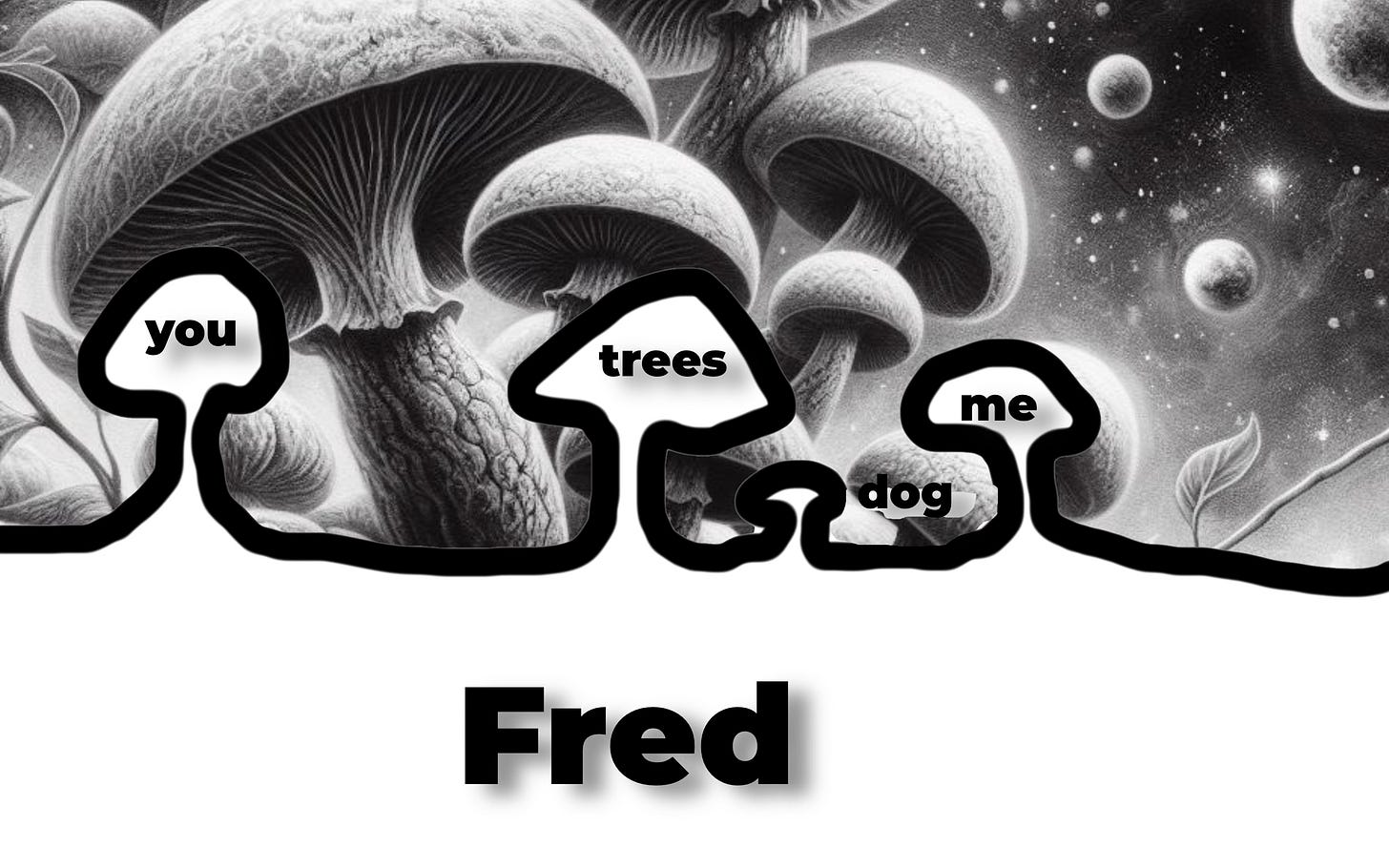

If I think that the fundamental of reality is consciousness, I think of it as a singular being - let’s call her Fred- manifesting fleetingly in this world as brief expressions like me, you, and everything else. A way to think about Fred is as an underground rhizome, connected to everything, and potentially the fundamental life-support of our ecosystems. Occasionally, a mushroom pops up—that's you.

If Fred is the rhizome, she would actually experience everything everywhere all at once. She would have a blast, because - unlike me - Fred actually gets everything. As a transient expression of Fred, it might be natural for me to yearn for that same wholeness, wanting to experience everything.

Perhaps, when I became a mushroom, I couldn't entirely shed Fred, retaining her inherent inclination for wanting everything. The idea that, at a deeper level, I am Fred is oddly reassuring when I contemplate all those things I long to experience but seemingly can't. I am already encompassing all those experiences—I just don't know it.

All four ideas don’t necessarily offer me very practical guidance on how to deal with my endless desires that - at their best - make life more interesting and - at their worst - contribute to harm through resource depletion and environmental impact.

At the same time, understanding the nature of desire helps me to find better possible solutions.

How I navigate my desires changes significantly depending on whether I view them as a purely biological impulse for a dopamine hit gone mad in a modern world, or if I see them as an inherent aspect of a purposeful universe. When I perceive desires as the former, I might try to suppress my desires, applying as much reason as possible (which rarely proves effective for me). Conversely, the latter might evoke a more compassionate response in which I “dance” with my desires, preferably salsa or a waltz.

Another beautiful piece. You will find much on this topic in Lacan. For instance his idea of jouissance and "surplus-enjoyement" as analogon of surplus-value. I published a book about that and what it means for capitalism but it's in French.

Oh and I am in for the university creation. A word that you barred in very Lacanian fashion.