How to Get Unstuck and Get Comfortable in the Void

Hello and welcome to wild:philosophy. It’s wonderful to “see” so many new faces.

If I were to say what I do, I’d say that I help people who deeply care about the whole and their part to understand how to live.

I am one of those people.

I care as much about my own part as I do about the whole.

I am constantly exploring this tension between the whole and my part. I want this life to be wonderful. I want it to be a piece of art, of beauty, of truth. Of the good. And the good is also always oriented towards the whole. How to combine all of that in the simple, mundane, everyday experience of being alive is the question that I am constantly exploring. Today’s essay is one of those explorations.

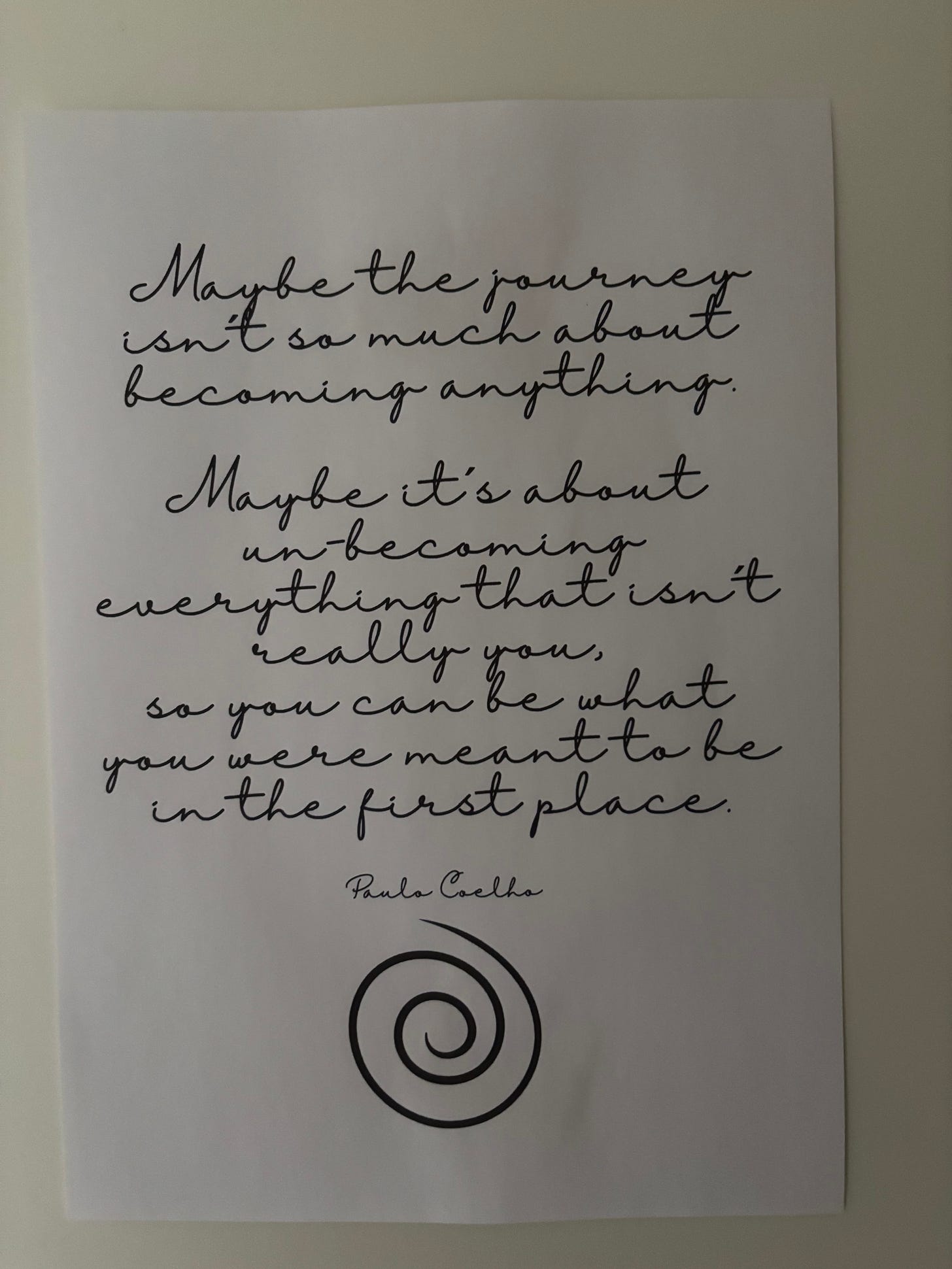

It often feels like we are stuck in our approach to a flourishing future, but getting unstuck is not about adding "unstucky" habits or "stuckless" strategies, but re-moving what we’re doing that’s keeping us there.

Caring for the self and the whole—a lot of times—is subtractive, not additive. Ending suffering is not about adding pleasure and joy or creating happiness, but about eliminating what we’ve learned to do that prevents those things. Philosophies of reductionism, determinism, anthropocentrism, and scientism, and their implications on how we think about progress, happiness, and the good life, are so pervasive in our everyday experiences that we hardly notice them. What if we stopped them?

As Bruce Lee would say,

"It is not a daily increase, but a daily decrease."

Sustainability, regeneration, and care for the whole, as well as care for the self, pragmatically have a lot to do with stopping or at least doing less of certain things:

flying

buying

distracting

mind-numbing technologies

living in a fantasy

being in denial

avoiding life

fixing ourselves

fixing the world

gossiping

martyring ourselves

attacking others

projecting

blaming

looking for a magic pill

othering

judging

reducing

controlling

anthropocentering

addictions

distorting reality

…

If we were to completely stop each of these things, the world would likely change very, very quickly.

I find the simplicity in this mind-boggling. And accessible. It means that busy people, those with real struggles in their daily lives, can benefit from it, too.

Less in my life

As I have recently written, I have long been striving for less.

If we strive for less, does that mean that we want more of less? So, in conclusion, we want more, too.

Anyways, I find that "less" is one of those things that sounds simple but doesn’t feel easy.

It’s not about more.

Which seems and feels very counterintuitive. And maybe that’s why it’s so hard.

Mark Gafni talks about our desire for more in terms of Eros: the deep yearning for the whole. For Gafni, Eros is not simply a desire for pleasure or accumulation, but a powerful, all-encompassing force that drives us towards connection, intimacy, and a sense of completeness. It is the pulse of evolution itself, a yearning for wholeness. This force is not a superficial want, but a call to participate in the fullness of being, to feel our entanglement with all of reality.

“Eros is wholeness and interconnectivity. It is the essential nature of a cosmos whose core truth might well be: reality is relationship. It is only when you realize that reality is relationship and that your relationship is part of the grand cacophony of relationship at every level of the cosmos that you truly transcend loneliness.” Mark Gafni

At the same time, when the whole seems to be attainable and we can easily make it ours, we lose resonance with it. It’s through the unattainability that we experience resonance, as Hartmut Rosa would say. Rosa argues that a meaningful, vibrant relationship with the world can only occur when the world speaks to us with its own voice, when it remains something we cannot fully control or possess.

The very moment the whole that Eros yearns for becomes completely graspable, it ceases to be a source of resonance and instead becomes a dead object of our domination. Rosa calls this quality Unverfügbarkeit—uncontrollability or unattainability. It is the untamed aspect of the world that allows us to be genuinely moved and transformed by it.

“This attitude can be observed even in situations where we do not seem to be focused on "conquest" at all—and not just latently, but in a manifest way. In party culture, for instance, buckets of alcohol are to be "destroyed" or "smashed," and in a choir, the goal is to "master" a difficult piece by Mendelssohn (flawlessly).

The everyday life of the average late-modern subject in the so-called "developed Western" world is increasingly centered on and exhausted by the task of working through exploding to-do lists. The entries on these lists become the "points of aggression" with which the world confronts us: the grocery shopping, the call to an aunt in need of care, the doctor's visit, work, the birthday party, the yoga class—all are tasks to be dealt with, procured, gotten out of the way, mastered, solved, or completed.

The world assails us in a historically unprecedented way. The notion—no, the conviction—that corresponds to these processes, inscribed in our bodies and our psychological and emotional dispositions, is this: What matters in life is making the world attainable.” Hartmut Rosa, translation with AI.

Thus, the deep yearning for the whole that Gafni describes is not a drive to conquer and consume (though this is what we have often made of it), but a call to enter into a responsive, dynamic relationship with a world that will always retain a measure of mystery.

So it’s not really about finally capturing the "more" that we seek, but rather about cultivating our capacity to be in a vibrant, reciprocal relationship with the wanting of more.

I love the yearning, the longing, the process of attaining. Biologically, this makes perfect sense.

Addictions, for instance, are less fueled by the pleasure of consuming the substance than by the dopamine hit that comes from the anticipation of it. Neuroscientists have shown that dopamine, often labeled the "pleasure molecule," is more accurately a "motivation molecule." Its primary role is not to create feelings of pleasure, but to drive us to seek out rewards. The dopamine spike associated with anticipating the reward is often far greater than the dopamine response from actually receiving it. Once the reward is obtained, the dopamine levels can quickly fall, sometimes even dipping below baseline, leaving a sense of flatness or wanting more.

Does that mean that wanting less is a pleasurable experience, until we actually have less? Maybe that’s why trying to wear one dress for life didn’t work.

The power of stopping

It’s easy to underestimate, dismiss, or ignore the simplicity of stopping.

Yet, making a choice to stop in the middle of suffering can be incredibly powerful.

When we are in the middle of defending, attacking, manipulating, lying, justifying, arguing, judging, or mindlessly consuming, seeing the behavior and making a genuine choice to stop it completely then and there is an ability that can change not just our own world, but the world.

How to Stop

Stopping is a choice. It’s not something we don’t already know how to do.

Depending on the situation, this can take a minute—or, for example with addictions or stopping a grudge towards someone, it can take years.

The process is typically described quite simply as:

Becoming aware of what we want to stop, let go of, or just do less of.

Making the choice to stop, let go, or reduce.

Stop, let go, or reduce.

Feel what comes up—whether pain or pleasure.

In his book The Untethered Soul, Michael Singer writes that letting go always only takes that very moment. Then it might come back and we have to let go again. And again. And again.

The stopping happens in an instant. There is no drama or effort.

The anxiety, evasion, and effort preceding the moment are another matter altogether.

It's the process surrounding the act of stopping—not the act itself—that demands our energy and time. When we create a drama around "trying so hard to stop," we're deceiving ourselves. This isn't really stopping or reducing, for that matter; it's creating a drama, a story.

Stopping, in its essence, is simple: it involves doing nothing.

When we claim that it is hard to stop, what we are often really referring to is the difficulty of confronting the elements linked to stopping, like relinquishing our dependencies, challenging our personal narratives, acknowledging the truth, or confronting our inner selves.

“My life is a mess just because this thing that lives in here with me has to make a melodrama out of everything.” Michael Singer

Yet, the struggle feels very real, and the only way I have found to deal with it is step four: “feeling whatever comes up” and, as practiced in many forms of meditation, accepting that feeling without judgment or a desire to change it.

What happens after we stop

Even if we make it through the struggle of stopping, even if we become experts at it and really let go of, let’s say, our anthropocentrism, what follows is empty space.

Depending on what we stop, that empty space might more closely resemble a void.

Especially when we stop holding onto certain belief systems.

If we are not the masters of the planet, who are we?

Empty space is not something many of us seem to be good at handling.

To me, it truly feels a bit terrifying.

We are creatures of the "more," and a void feels like a failure. It feels like death. We rush to fill it with the next distraction, the next belief system, the next project of "fixing," because the silence is deafening. It forces a confrontation with the raw, unmediated reality we’ve often spent our lives trying to control or escape.

But what if this empty space, this void, is not the end of the story?

What if being in the emptiness becomes the ultimate act of stopping? What if we get cozy in the void?

If we stop our need to always be filling, doing, and becoming.

Likely, it is here where resonance can actually emerge.

We cannot form a new, responsive relationship with the world when we are filled with automated responses. The world can only speak to us in a voice of its own when we have stopped talking. The emptiness of the void might be the space where we can at last hear something.

So, caring for ourselves and the whole is (among other things) a radical commitment to this emptiness. It is stopping carried to its conclusion. It is trusting that when we stop everything that keeps us from a flourishing future, we might not need to add a single new strategy. We “simply” need to stand in the emptiness we’ve created and allow the world, in all its wild and uncontrollable beauty, to reach us. Practicing philosophy is a practice of gettin’ comfi in the emptiness.

If you like my writing, I’d deeply appreciate if you click the 🖤 or 🔄 button on this post so more people can discover it 🙏.

I love your list of "less is more"! Can I use it by giving you credits? I would definitely add "chat with AI bots" =) though..

Have you read First Principles & First Values by David J. Temple (Marc Gafni et al)? You touch on his Cosmoerotic Humanism theory here, but I was just wondering. I found it really interesting, even if a bit hard to follow at times.

Daniel Schmachtenberger provided a beautiful sort of primer to the whole thing in his speech at the Emergence Festival though, which is what got me into it in the first place.

Anyway, always a nice read. :)